An Elephant Researcher Never Forgets

Andrew Schulz takes an inclusive approach to his innovative research on elephant biomechanics

October 16, 2020 | By Kristin Baird Rattini

Q. How do you know when an elephant is leaving on a trip?

A. It has packed its trunk.

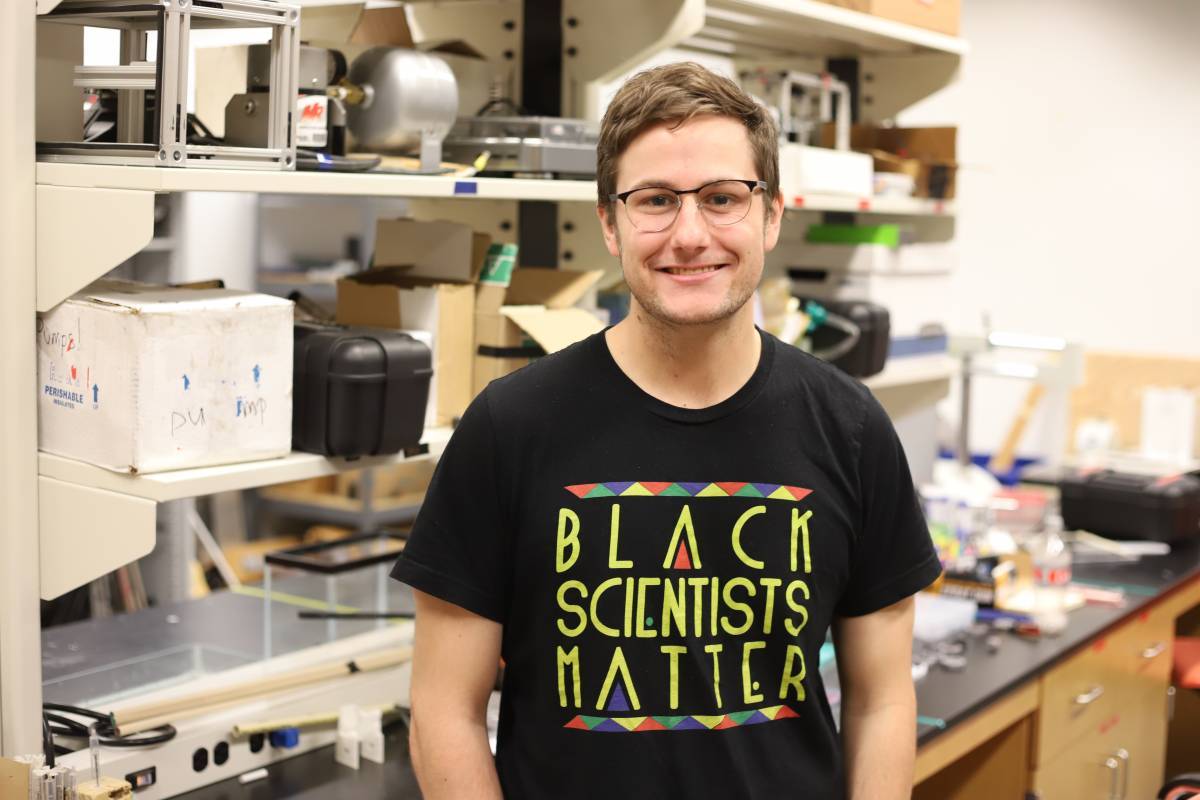

Andrew Schulz is dedicated to unpacking the elephant trunk. The Ph.D. student in mechanical engineering is scrutinizing the biomechanics of the pachyderm’s muscular marvel and translating his discoveries into not only robotic applications but also conservation measures to safeguard African elephants in the wild. Through his research in mechanical engineering Professor David Hu’s Laboratory for Biolocomotion, collaborations with Zoo Atlanta, outreach with an elephant sanctuary in South Africa and creation of the GaTech4Wildlife course, Schulz is a role model for research that’s equally innovative and conscientious.

When I started my work, I wanted to avoid the path that a lot of traditional research into large animals has taken, called parachute science,” he explains. “It’s when a scientist drops in to a location, takes up the time of the people on the ground who know the situation best, and then leaves without giving them credit or sharing the results or resources they helped create. It’s a big problem. I didn’t just want to address it myself, but educate others on how we can take a better approach.

Schulz is a docent at Zoo Atlanta

Schulz’s fascination with the Loxodonta africana, or African bush elephant, began as a high schooler while on a safari in South Africa. “It was sheer awe,” he says. “You realize just how large they are in every respect.” That includes the trunk, which measures between six to nine feet in length and weighs up to 330 pounds. Scientists are still researching the number of muscles in the trunk; estimates have ranged from 30,000 to 150,000. (Humans have around 600). The trunk has no bones or joints but does have a second “finger” at its tip, which works as an opposable thumb for grasping objects and can pick up an object as small and delicate as a tortilla chip without breaking it. Schulz’s research strives to understand how the trunk is able to maneuver in such varying and complex ways.

Through his studies of a female African elephant named Kelly at Zoo Atlanta, Schulz discovered that the trunk can elongate 25 percent longer than its hanging length. “That might not seem like much,” he says, “but it’s the equivalent of growing from the height of actor Kevin Hart, who is 5 feet, 4 inches tall, to basketball player LeBron James, who is 6 feet, 8 inches tall.” The secret to the stretch seems to lie not just in the trunk’s muscles but also in its folds of slack skin, which appears to provide protection from heavy forces or loads. “This contributes to the trunk’s ability to be both flexible and strong,” he says. That combination is crucial in the development of “soft robotics” that use materials such as silicone instead of metals.

As a two-term president of the Mechanical Engineering Graduate Association, Schulz has strived to create an inclusive and supportive environment for students of all backgrounds.

Schulz’s research could also be used to help reduce negative human-elephant interactions in the wild. For example, farmers could install fences at spots that put crops beyond the reach an outstretched, versus a hanging, trunk. Schulz focuses on creating such research-driven solutions for real-world problems faced by conservationists in GATech4Wildlife, a course he designed and teaches through the VIP (Vertically Integrated Projects) Program. The program brings together undergraduates from various disciplines, years and backgrounds to work with faculty and graduate students on long-term, large scale projects. The GATech4Wildlife students work in teams – in consultation with conservation experts – to develop interventions to aid in the preservation of various species. “We draw together engineers, scientists, business majors and other students from across the Georgia Tech campus to develop these interdisciplinary projects that benefit wildlife conservation,” he explains.

This “all are welcome” approach is a core value for Schulz. As a two-term president of the Mechanical Engineering Graduate Association, he has strived to create an inclusive and supportive environment for students of all backgrounds. In his own research as well as his students’ projects, he makes a concerted effort to closely work with all the stakeholders on the ground in Africa and elsewhere. His students are currently collaborating with the director of Adventures with Elephants, an elephant reserve in South Africa, to develop additional interventions to reduce negative human-elephant interactions.

Studying elephants requires a huge team of people, and Andrew is a natural leader of this team,” says Hu, Schulz’s advisor, and director of the Hu Lab. “He’s the glue holding this project together.

Schulz and his students have other projects beyond the elephant kingdom. He’ll translate his research into panda climbing biomechanics into an app that enables panda handlers in China to assess the climbing skills of panda cubs. His class is evaluating the wildlife ecosystem on the Georgia Tech campus and contemplating how the use of camera traps baited with medicated biscuits could vaccinate foxes for rabies. They’re also developing inexpensive feeders for gorillas at Zoo Atlanta, where Schulz spends his time not only as a researcher but as a volunteer docent. “The keepers have given me so much of their time,” he says. “It’s important to me to give back to all of the organizations that help with my research.”

The time he spends at the zoo – with not only the animals and keepers but the visitors he educates -- further fuels Schulz’s conservation mission. “It makes you want to figure out how you can use your skills and resources to help save these species,” he says. “For me, that’s through engineering. I want to inspire other engineers to apply the tools they’ve learned through Georgia Tech to help preserve these magnificent animals for future generations.”

To learn more about Schulz’s research visit schulzscience.com.