Research Out Front: Looking Ahead to 2023

December 21, 2022

By Benjamin Hodges and Steven Norris

As we transition to a new year, researchers across the globe are looking ahead to the world’s most pressing concerns. Experts at Georgia Tech are hard at work trying to understand how these unfolding issues will play out over the next 12 months. As we wrap up 2022 and begin 2023, we’re looking at six young, pioneering Georgia Tech researchers who are tackling some of the world’s most complicated issues and working on solutions ranging from feeding an ever-growing population to controlling wheelchairs via wireless brain wave patches. Here’s a closer look at what W. Hong Yeo, associate professor and Woodruff Faculty Fellow in the George W. Woodruff School of Mechanical Engineering, will be watching over the next 12 months and beyond.

Modern medicine has come a long way in the past century, eradicating diseases and treating formerly life-threatening conditions with outpatient procedures. But when it comes to the technology used in clinical settings for health monitoring and diagnostics — the machines doctors rely on to measure heart activity and sleep patterns, for example — much of it hasn’t changed in decades.

“A lot of the medical devices doctors use are still very far behind from a technological standpoint,” says W. Hong Yeo, associate professor of mechanical engineering and director of the Center for Human-Centric Interfaces and Engineering. “They’re not meeting the needs of patients, and they’re not meeting the needs of clinicians.”

Yeo is on a mission to redefine these clinical experiences — to overcome their limitations, making them easier and more comfortable for patients while also yielding more reliable and more comprehensive data. His Bio-Interfaced Translational Nanoengineering Group balances more than 20 funded projects at a time, with the goal of bringing bring medical monitoring and diagnostics up to date using emerging advances in soft robotics, nanotechnology, and bioelectronics.

So many of our current systems for monitoring and diagnostics rely on bulky machines that enmesh motionless patients in a snarl of wires and sensors, Yeo says. Cardiac tests like the electrocardiogram can’t provide continuous data, and they only work if patients remain still and do nothing. Sleep studies, on the other hand, subject patients to uncomfortable, atypical environments prone to yield suspect data. These dependencies on motionlessness and unnatural settings activity make the tests highly susceptible to error and limit the value and trustworthiness of their data.

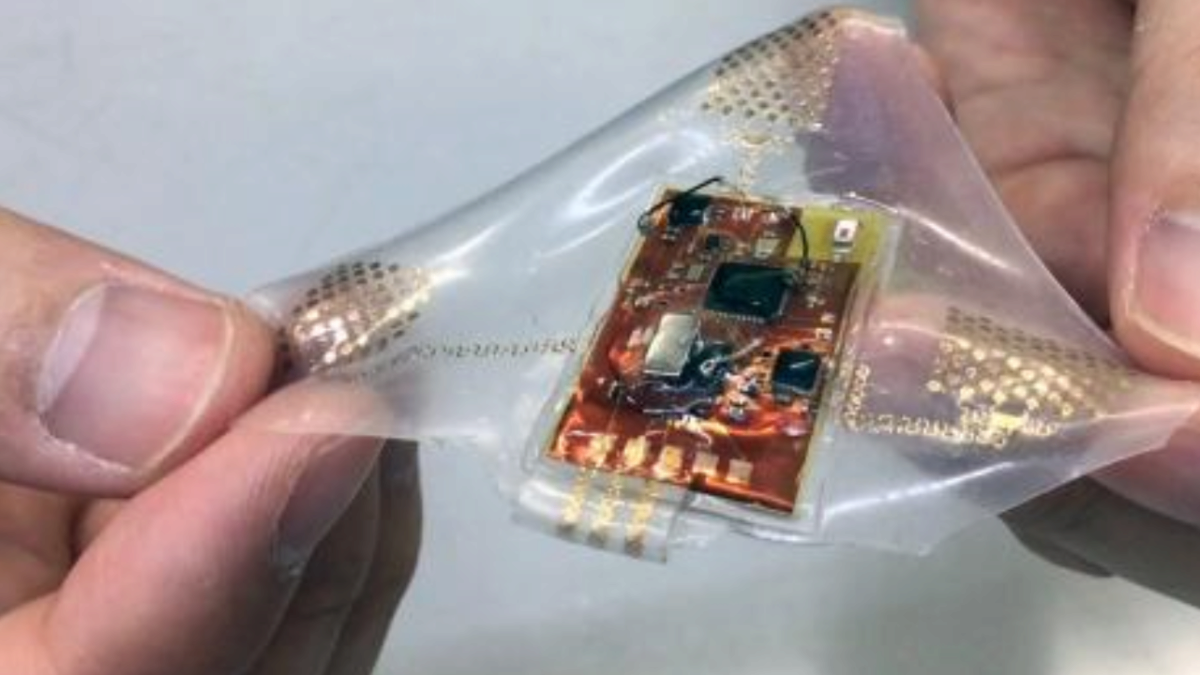

To address these challenges and limitations, Yeo’s group designs and manufactures nano-biosensors and bioelectronics. Completely wireless and easy to wear, these “biopatches” look like small stickers or bandages — soft and tiny, flexible and imperceptible — and a single device can track heart rate and other cardiac activity, respiration, blood oxygen concentration, body temperature, brain activity, and more.

Yeo, who has also founded two biomedical startups, is working through the multiyear process of obtaining FDA approval for his devices to be used in clinical settings. He hopes the technology can transform the health screening experience for patients and doctors alike — and also save the lives of people like his father, who died from a heart attack in his sleep despite his excellent health and with no family history of cardiac disease.

“This is going to be good for everybody,” he says. “It will save time and money on both sides — for patients as well as providers and insurance companies. It will also increase the efficiency of our hospitals, which will be able to devote their resources to people who need treatment, and help clinicians identify abnormalities early on.”

W. Hong Yeo is a Woodruff Faculty Fellow, associate professor in the George W. Woodruff School of Mechanical Engineering and the Wallace H. Coulter Department of Biomedical Engineering, and the director of the Center for Human-Centric Interfaces and Engineering.