Why did the gecko climb the skyscraper? Because it could; its toes stick to about anything. Engineers can already emulate the secrets of gecko stickiness to make strips of rubbery materials that can pick up and release objects, but simple mass production for everyday use has been out of reach until now.

Researchers at the Georgia Institute of Technology have developed, in a new study, a method of making gecko-inspired adhesive materials that is much more cost-effective than current methods. It could enable mass production and the spread of the versatile gripping strips to manufacturing and homes.

Polymers with “gecko adhesion” surfaces could be used to make extremely versatile grippers to pick up very different objects even on the same assembly line. They could make picture hanging easy by adhering to both the picture and the wall at the same time. Vacuum cleaner robots with gecko adhesion could someday scoot up tall buildings to clean facades.

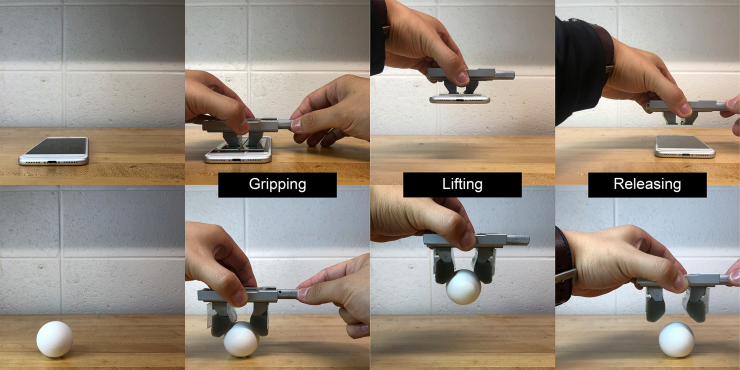

“With the exception of things like Teflon, it will adhere to anything. This is a clear advantage in manufacturing because we don’t have to prepare the gripper for specific surfaces we want to lift. Gecko-inspired adhesives can lift flat objects like boxes then turn around and lift curved objects like eggs and vegetables,” said Michael Varenberg, the study’s principal investigator and an assistant professor in Georgia Tech’s George W. Woodruff School of Mechanical Engineering.

Current grippers on assembly lines, such as clamps, magnets, and suction cups, can each lift limited ranges of objects. Grippers based on gecko-inspired surfaces, which are dry and contain no glue or goo, could replace many grippers or just fill in capability gaps left by other gripping mechanisms.

The slightest bit of shear tension makes gecko adhesion surfaces grip, and the release of that same tension makes them let go. The same gripping surfaces can pick up objects of all shapes, sizes, and materials with the exception of Teflon and other non-stick surfaces. Credit: Georgia Tech / Varenberg lab

Drawing out razors

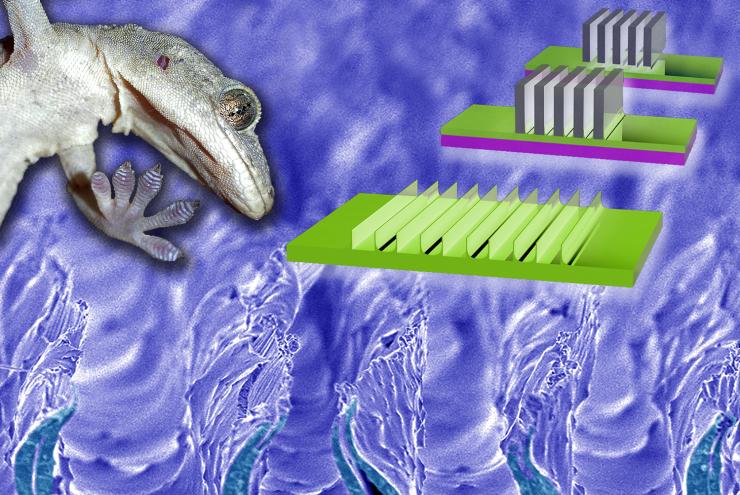

The adhesion comes from protrusions a few hundred microns in size that often look like sections of short, floppy walls running parallel to each other across the material’s surface. How they work by mimicking geckos’ feet is explained below.

Up to now, molding has produced these mesoscale walls by pouring ingredients onto a template, letting the mixture react and set to a flexible polymer then removing it from the mold. But the method is inconvenient.

“Molding techniques are expensive and time-consuming processes. And there are issues with getting the gecko-like material to release from the template, which can disturb the quality of the attachment surface,” Varenberg said.

The researchers’ new method formed those walls by pouring ingredients onto a smooth surface instead of a mold, letting the polymer partially set then dipping rows of laboratory razor blades into it. The material set a little more around the blades, which were then drawn out, leaving behind micron-scale indentations surrounded by the desired walls.

Varenberg and first author Jae-Kang Kim published details of their new method in the journal ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces on April 6, 2020.

Forget about perfection

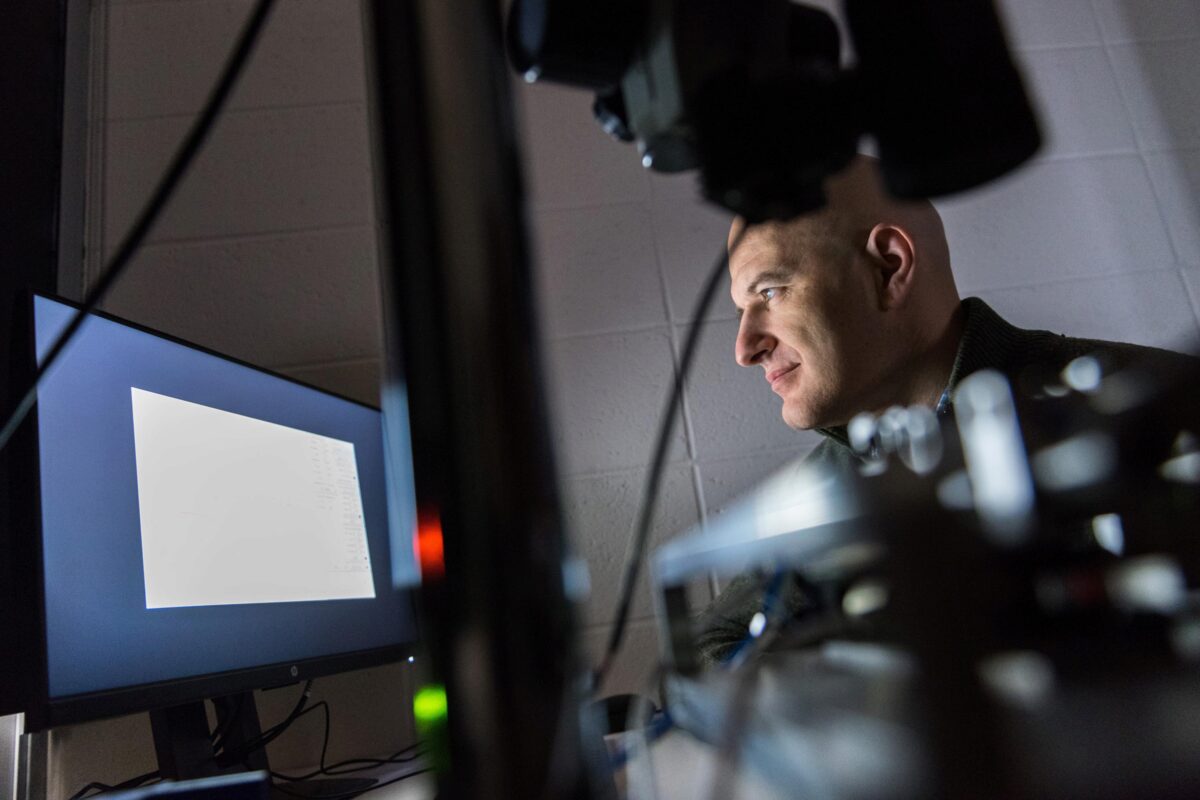

Though the new method is easier than molding, developing it took a year of dipping, drawing, and readjusting while surveying finicky details under an electron microscope.

“There are many parameters to control: Viscosity and temperature of the liquid; timing, speed, and distance of withdrawing the blades. We needed enough plasticity of the setting polymer to the blades to stretch the walls up, and not so much rigidity that would lead the walls to rip up,” Varenberg said.

Gecko-inspired surfaces have a fine topography on a micron-scale and sometimes even on a nanoscale, and surfaces made via molding are usually the most precise. But such perfection is unnecessary; the materials made with the new method did the job well and were also markedly robust.

“Many researchers demonstrating gecko adhesion have to do it in a cleanroom in clean gear. Our system just plain works in normal settings. It is robust and simple, and I think it has good potential for use in industry and homes,” said Varenberg, who studies surfaces in nature to mimic their advantageous qualities in human-made materials.

Michael Varenberg, an assistant professor in Georgia Tech's George W. Woodruff School of Mechanical Engineering.

Gecko foot fluff

Behold the gecko’s foot. It has ridges on its toes, and this has led some in the past to think their feet stick by suction or some kind of clutching by the skin.

But electron microscopes reveal a deeper structure – spatula-shaped bristly fibrils protrude a few dozen microns long off those ridges. The fibrils make such thorough contact with surfaces down to the nanoscale that weak attractions between atoms on both sides appear to add up enormously to create overall strong adhesion.

In place of fluff, engineers have developed rows of shapes covering materials that produce the effect. A common shape makes a material’s surface look like a field of mushrooms that are a few hundred microns in size; another is rows of short walls like those in this study.

“The mushroom patterns touch a surface, and they are attached straightaway, but detaching requires applying forces that can be disadvantageous. The wall-shaped projections require minor shear force like a tug or a gentle grab to generate adherence, but that is easy, and letting go of the object is uncomplicated, too,” Varenberg said.

Varenberg’s research team used the drawing method to make walls with U-shaped spaces in between them and walls with V-shaped spaces in between. They worked with polyvinylsiloxane (PVS) and polyurethane (PU). The V-shape made in PVS worked best, but polyurethane is the better material for industry, so Vanenberg’s group will now work toward achieving the V-shape gecko gripping pattern in PU for the best possible combination.

The inset on the upper right illustrates how the gecko adhesion surface is made by pushing lab razor blades into a setting polymer. The razor blades are pulled out, leaving indentations and stretching some of the polymer up, resulting in flexible walls that produce the gecko adhesion effect. Credit: Georgia Tech / Varenberg lab

Writer & Media Representative: Ben Brumfield (404-272-2780), email: ben.brumfield@comm.gatech.edu

Georgia Institute of Technology